Trigeminal Neuralgia

- Home

- Conditions

- Headaches

- Trigeminal Neuralgia

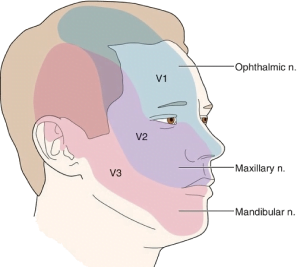

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is defined by recurrent unilateral brief electric shock-like pain in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve, which is abrupt in it’s onset and termination. The pain is restricted to one or more of the trigeminal divisions and is triggered by innocuous sensory stimuli. TN is divided into either classical TN (CTN) or secondary TN (STN) caused by multiple sclerosis or a space-occupying lesion such as a tumor, cerebral aneurism or a megadolicho basilar artery.

Treatment for Trigeminal Neuralgia

Epidemiology

TN is frequently both misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed. The incidence of TN is variably reported between studies, with a range from 4.3 to 27 new cases per 100,000 people per year. The incidence is higher among women, and increases with age. The lifetime prevalence was estimated to be 0.16–0.3% in population-based studies. The average age of onset is 53 years in classical TN and 43 years in secondary TN, but the age of onset can range from early to old age. In tertiary care-based studies, STN accounted for 14–20% of TN patients.

Etiology & Pathogenesis

Dandy proposed as early as 1930 that conservatively speaking the cause behind 30% of the patients a licted with Trigeminal Neuralgia was due to compression of the trigeminal nerve by a blood vessel. As of today the consensus behind the etiology of Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia is either compression or morphological changes in the trigeminal nerve brought about usually an artery in the cerebellopontine cistern. This is termed as ‘NEUROVASCULAR CONFLICT’ with compression. Transition of Schwann cell myelination to oligodendroglia myelination was observed in many anatomical specimens.

Evidence in recent times is in favor of a neuromuscular conflict characterized by neurovascular conflict involving morphological changes of distortion, distension, indentation, dislocation , flattening or atrophy of the trigeminal nerve is a hallmark feature of up to half the patients suffering from Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Conversely, there is a line of thought whether ‘simple contact’ between structures might play a role in the etiology.

Various studies point towards focal demyelination of primary trigeminal afferents adjacent to the entry of the root of the trigeminal nerve into the pons, as the chief underlying pathophysiology in people suffering with Trigeminal Neuralgia. In Secondary TN, though the pathophysiological mechanism is the same as Classical TN, the etiology is governed by different structural lesions such as plaques of Multiple Sclerosis affecting the trigeminal root or a space-occupying lesion in the cerebellopontine cistern such as epidermoid tumors, meningiomas, neurinomas, arteriovenous malformations or aneurysms.

Symptom Complex of Trigeminal Neuralgia

The original term coined for this condition was Tic Doloureux, keeping in mind the characteristic wince seen in TN patients at the time of a pain paroxysm.

The pain has been described by patients as being of a sharp, shooting and stabbing in nature and mimicking electric shock- like sensations. The pain paroxysm of Trigeminal Neuralgia is an extremely painful and debilitating experience for the system. The sudden and unexpected onset makes this highly unpleasant pain even more horrifying for patients. A Pain Paroxysm can last from a fraction of a second to several times a day because these paroxysms are sometimes set into continuous recurrence following a refractory period. This may be experienced as a series of attacks with many paroxysms punctuating close together. The paroxysmal pain may be accompanied by a continuous pain of a dull achy nature in the background and milder in intensity. This background headache has been observed more commonly in women.

Refractory period and trigger factors

Patients usually experience a refractory period following the paroxysmal attack where another attack cannot be triggered. Hyperpolarisation of the sensory neuron has been deemed responsible for this phenomena. Many patients experience a refractory period after a paroxysmal attack where new attacks cannot be elicited. The pathophysiological mechanism of this phenomenon is unknown. It has been proposed that it is caused by hyperpolarization of the sensory neuron. Kugelberg and lindbom, in their studies have drawn a direct relationship between the presence and duration of refractory period to the intensity and duration of the concluded attack. The pain of Trigeminal Neuralgia may be triggered by innocuous sensory stimuli to the side of the face. The stimuli might be intramural or extra oral. The commonly seen triggers include normal daily activities such as light touch, talking, chewing, brushing teeth and cold wind against the face.

Site of lesion

The second or third division of the trigeminal nerve is most commonly a ected. Right side is a ected more often. Bilateral TN is rare in the classical form and should be indicative of a case of Secondary TN.

Natural Progression

It was earlier strongly believed that the pain of TN worsens over time and becomes chronic characterised There are very few studies examining the natural history of TN. It has been proposed that pain may worsen with time and that TN in its chronic state is characterised by longer lasting, medically refractory pain, sensory disturbances and progressive neuroanatomical changes of the trigeminal root. In recent times, studies have challenged this belief by showing that in majority of patients, the pain did not increase in frequency or duration, nor did it become refractory to medication and even the dosage threshold remained more or less constant. Another common observation is periods of complete remission lasting for months and in some cases even years. This can be attributed to reduction in nerve excitability and partial demyelination.

Facial pain associated with autonomic features

Tearing and rhinorrhea have been long associated with TN . Autonomic symptoms are part of the symptom complex in a majority of TN patients. [26,27,29] This is believed to be the result of the trigeminovascular reflex which tends to get elicited by intense facial pain. The differential diagnosis include short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT), and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with autonomic symptoms (SUNA).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of TN is essentially based on the history . The onset of pain is a very important component of the history taking . History of any preceding Herpes Zoster rash in the affected area, any invasive dental procedures or significant trauma to the ipsilateral side of the face is a must. A dental procedure or trauma can point towards Post Traumatic Trigeminal Neuropathy(PPTN). PPTN may be comparable to TN but it is marked by clear cut sensory abnormalities.

TA thorough dental check-up is warranted to rule out a cracked tooth(probably due to chewing hard foods), which might present like the pain of TN. Bilateral constant pain in the jaw area might raise the possibility of tension-type headache, temporomandibular joint disorder and persistent idiopathic facial pain. Other differential diagnosis include Occipital neuralgia, paroxysmal hemicrania, glossopharyngeal neuralgia , short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection and tearing (SUNCT), and short-lasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with autonomic symptoms (SUNA)

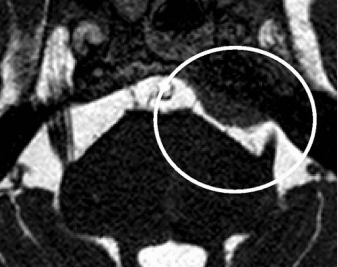

Though primarily a clinical diagnosis, Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging can detect changes in trigeminal root, any neuromuscular compression and to rule out secondary pathology. MRI can diagnose entire course of nerve, root atrophy, and CPA cistern. 3D fast imaging employing steady-state acquisition(FIESTA) and contrast-enhanced 3D time-of-flight (TOF) magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) in combination with unenhanced MRA are becoming popular in detecting the vessel involved and in detecting the vascular conflict.

Treatment

Abortive treatments haven’t been successful for managing Trigeminal Neuralgia but the mainstay remains pharmacological management. Ablative and non-ablative interventional procedures are reserved for patients for medical management fails to control the symptoms.

- Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine : The first- line management offered to patients suffering with TN are Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. They are seen to be effective in delivering initial pain control in up to 90% of the patients although the effects may unfortunately wane down with chronicity. The potent side effect profile of these drugs leads to withdrawal of their use in up to 40% of the patients. Women are less tolerant to these medications. Carbamazepine use in patients with other significant comorbidities is difficult as it tends to have interactions with other medications. Oxcarbazepine, though causes fewer side effects, can bring about central nervous system depression or dose related hypernatremia. ( decreased sodium) Clinical response to both drugs differs in patients considerably. One can be replaced with the other to get a better response. ‘200 mg of carbamazepine is equipotent to 300 mg of oxcarbazepine’. While the effects of these drugs are significant in the control of paroxysmal pain

- Lamotrigine : Lamotrigine is generally recommended as an add-on therapy for patients showing poor tolerance to carbamazepine and oxcarbezepine. It is generally associated with fewer side effects than carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine

- Gabapentin and pregabalin : Clinical application has shown gabapentin and pregabalin to be less effective but having fewer side effects than carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine. They can therefore be used in place of or in addition to carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine. However, they do pose a risk of dependency.

- Baclofen : Baclofen is particularly helpful in patients with a background of Multiple Sclerosis where it might be used for managing spasticity.

- Botulinum toxin type A : Recent studies focussing on the e icacy of subcutaneous injection and injection over the gingival mucosa (of Botulin Toxin Type A) , found significant improvement in symptoms as compared to placebo. Transient facial edema and and transient facial weakness were some of the mild side effects.

Acute Treatment for Severe Exacerbation

Severe exacerbations ,which are marked by intense painful episodes with increasing frequency and di iculty in even eating or drinking are managed by hospital admission for immediate rehydration, maintenance of nutrition, short-term pain management and long-term optimisation of preventive treatments. Opioids are often used during such episodes but their e icacy has been questioned. Local anaesthetic injections or topical lidocaine can be effective for instantly reducing the pain from trigger zones. Intravenous infusions of fosphenytoin (15 mg/kg over 30 min) and lidocaine (5 mg/kg over 60 min) under cardiac monitoring can be highly effective.

Non Surgical Interventional Treatments :

These are considered for debilitating pain refractory to medicines. They can be divided into

- Needle based Controlled Radiofrequency lesioning of the trigeminal ganglion.

- Mechanical ballon compression of the trigeminal ganglion.

- Glycerol based chemical rhizolysis

- Internal Neurolysis- Separation of the trigeminal nerve fascicles in the posterior fossa.

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery focussing radiation at the trigeminal root entry zone.

At Alleviate

For patients not responding to medical management the treatment of choice is, Image guided Controlled Radiofrequency Lessoning of the Trigeminal Ganglion. Surgical intervention for trigeminal neuralgia Patients not responding to any of the above stated treatment modalities are faced with the surgical option of Micro vascular decompression. Surgeon has to be really careful due to the proximity of neurovascular structures to the operating field. Micro vascular decompression has better results in elderly with fewer co-morbidities as opposed to the younger population.

FAQs - Trigeminal Neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a painful type of neuralgia that affects the trigeminal nerve. TN can occur in any sensory nerve (nerve) but is commonly found affecting the nerves of the face, head, and neck.

The trigeminal nerve is the fifth cranial nerve. It is responsible for maintaining balance and is also responsible for transmitting pain signals from the face to the brain. Located on the jaw side of the face, it is responsible for transmitting pain from the face, teeth, and eyes to the brain.

Trigeminal Neuralgia (TN) is a very painful disorder that affects the trigeminal nerve. As the name suggests, it is caused by an inflammation of the trigeminal nerve. There are several conditions that cause severe pain in the area of your face and head, making you feel like you are being stabbed by something sharp and hot, and extremely painful. It is triggered because a small part of the trigeminal nerve is trapped under the skull, causing the nerve to become irritated and release extremely painful muscle-twitching spasms.

It can be a severe and severe form of facial pain that affects the trigeminal nerve. The pain appears in the face and is characterized by burning pain and numbness.

There are two main types of trigeminal neuralgia (TN) - classical TN (CTN) or secondary TN (STN) caused by multiple sclerosis or a space-occupying lesion such as a tumor, cerebral aneurism, or a megadolicho basilar artery.

The symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia are described as sharp, electric-like shooting pain in the face or head around the eyes, ears, nose, upper lip, and forehead.

The other symptoms include:

- pain paroxysm – an extremely painful condition

- sudden and unexpected onset with high intense pain

- pain that occurs in the same place on both sides of the face or head

- a severe pain that lasts from several seconds to a few minutes

- a sudden or sudden pressure on the face, such as by sneezing, brushing teeth, or head trauma

A doctor will ask about your symptoms, medical history, and any medications you are taking. The doctor may also do a physical exam. An imaging test, such as an MRI, may also be done. A thorough dental checkup cannot be ruled out as well

Other differential diagnoses include:

- Occipital neuralgia

- Paroxysmal hemicrania,

- Glossopharyngeal neuralgia

Trigeminal neuralgia is a chronic pain disorder that causes episodes of facial pain. Usually, treatment involves controlling the pain with medications, a procedure called nerve block or surgery, or a combination of both medications and surgery.

The types of medications involved are:

- Carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine

- Lamotrigine

- Gabapentin and pregabalin

- Baclofen – a muscle relaxant

- Botulinum toxin type A – a subcutaneous injection

Patients with intense painful episodes are often provided with Optiods. Local anaesthetic injections or topical lidocaine can be effective to bring down the pain from the triggering points.

For debilitating pain refractory to medicines, non-surgical treatment is given which includes:

- Needle based Controlled Radiofrequency lesioning

- Mechanical ballon compression

- Glycerol based chemical rhizolysis

- Internal Neurolysis

- Stereotactic Radiosurgery

A highly-experienced pain management is specialized to provide Controlled Radiofrequency Lesioning of the Trigeminal Ganglion. At Alleviate Pain Clinic, you will find an image-guided non-surgical treatment approach conducted by the medical management specialist.

Surgical treatment is determined if patients failed to respond to medications and non-surgical approaches. There are different modalities with the surgical option of Microvascular decompression, and a highly experienced surgeon conducts the treatment to yield better results.

Video Spotlight

Blog

Surgery-Free Solutions

Expert Tips for Pain Management

Testimonials

Words From Our Patients

The treatment was very good and the doctor Faraz Ahmed was very kind to the patient and explained clearly the procedure of knee bilateral ha & botox And we were advised to do physiotherapy. We are very much satisfied. We would recommend this alleviate pain clinic.Thank you

Got treatment of Botox and HA for right knee arthritis a month ago and finding good relief from pain. Was treated by Dr Swagtesh Bastia who explained very well about the injections and the treatment was painless. The front desk staff were very kind and very helpful and physiotherapy was also done expertly, overall good experience

Alleviate Pain Management clinic has been a godsend for my mom's knee pain. She has been treated by Dr. Wiquar Ahmed. The attentive staff provided personalised care, and after her treatment, she's feeling remarkably better. Thank you for giving my mom the relief she deserves!

The clinic is super clean with a great OT and most importantly all the staff here are very helpful and considerate. My gratitude to Dr Roshan, the nurses, and support staff - they were always available to assist with any issues post procedure and they even made an extra effort to make a home visit for a follow up check-up. This team here is the perfect example of healing and care with a human touch. Thank you!!!!!

My wife had knee pain I have visited alleviate pain and consulted doc santhoshi now she is able to walk pain free and can do her daily activity than before.the physiotherapist here Dr akhila also helped her with few exercises and the staff here Abdul explained all the procedures well . Thank you PPL can visit here for pain relief